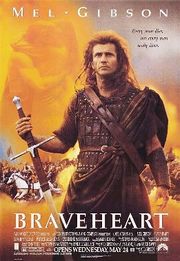

Braveheart

| Braveheart | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Mel Gibson |

| Produced by | Mel Gibson Alan Ladd, Jr. Bruce Davey Stephen McEveety |

| Written by | Randall Wallace |

| Narrated by | Angus Macfadyen |

| Starring | Mel Gibson Patrick McGoohan Angus Macfadyen Brendan Gleeson Sophie Marceau Ian Bannen James Cosmo Catherine McCormack David O'Hara Brian Cox |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | John Toll |

| Editing by | Steven Rosenblum |

| Studio | Icon Productions 20th Century Fox Paramount Pictures |

| Distributed by | United States: Paramount Pictures International: 20th Century Fox |

| Release date(s) | May 24, 1995 |

| Running time | 177 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $72,000,000 |

| Gross revenue | $210,409,945 |

Braveheart is a 1995 American epic drama film directed by and starring Mel Gibson. The film was written for the screen and then novelized by Randall Wallace. Gibson portrays William Wallace, a Scottish warrior who gained recognition when he came to the forefront of the First War of Scottish Independence by opposing King Edward I of England, also known as "Longshanks" (Patrick McGoohan).

The film won five Academy Awards at the 68th Academy Awards, including the Academy Award for Best Picture and Best Director, and had been nominated for an additional five.

Contents |

Plot

In 1280 A.D., King Edward "Longshanks" (Patrick McGoohan), has occupied much of southern Scotland, and his oppressive rule there leads to the deaths of William Wallace's father and brother. Years later, after Wallace has been raised abroad by his uncle (Brian Cox), the Scots continue to live under the iron fist of Longshanks' cruel laws. Wallace returns, intent on living as a farmer and avoiding involvement in the ongoing "troubles". Wallace seeks out and courts Murron, and the two marry in secret to avoid the decree of primae noctis the King has set forth. When an English soldier tries to rape Murron, Wallace fights off several soldiers and the two attempt to flee, but the village sheriff captures Murron and publicly executes her by slitting her throat, proclaiming "an assault on the King's soldiers is the same as an assault on the King himself." In retribution, Wallace and several villagers slaughter the English garrison, executing the sheriff in the same manner that he executed Murron.

Wallace, the men from his village, and a neighbouring clan enter the fortress of the local English lord, killing him and burning it down. In response to Wallace's exploits, the commoners of Scotland rise in revolt against England. As his legend spreads, hundreds of Scots from the surrounding clans volunteer to join Wallace's militia. Wallace leads his army through a series of successful battles against the English, including the Battle of Stirling Bridge, and the sacking of the city of York. All the while, Wallace seeks the assistance of young Robert the Bruce (Angus Macfadyen), son of the leper noble Robert the Bruce (Ian Bannen) and the chief contender for the Scottish crown. However, Robert is dominated by his scheming father, who wishes to secure the throne of Scotland to his son by bowing down to the English, despite his son's growing admiration for Wallace and his cause.

Two Scottish nobles, Lochlan and Mornay, planning to submit to Longshanks, betray Wallace at the Battle of Falkirk. The Scots lose the battle and Wallace nearly loses his life. As a last desperate act a furious Wallace breaks ranks and charges toward Longshanks, who led the English troops. He is intercepted by one of the king's hooded lancers and knocked from his horse, but gains the upper hand when the lancer dismounts to examine the fallen Wallace. Wallace is set to kill the lancer, but upon taking the lancer's helmet off, discovered his opponent is Robert the Bruce. Bruce is able to get Wallace to safety just before the English can capture him, but laments his actions for some time to come because of what Wallace has stood for, which he betrayed.

For the next seven years, Wallace goes into hiding, fighting a guerrilla war against English forces with his remaining band of Scotsmen. In order to repay Mornay and Lochlan for their betrayals, Wallace brutally murders both men: Mornay by crushing his skull with a mace in his bed chamber and Lochlan by slitting his throat during a meeting of the nobles at Edinburgh. Meanwhile, Princess Isabelle of France (Sophie Marceau) (whose incompetent husband Edward, Prince of Wales ignores her) meets with Wallace as the English king's emissary. Having heard of him beforehand and after meeting him in person, she becomes enamored with him and secretly assists him in his fight. Eventually, she and Wallace make love, after which she becomes pregnant. Still believing there is some good in the nobility of his country, Wallace eventually agrees to meet with Robert the Bruce in Edinburgh. Wallace is caught in a trap set by the elder Bruce and the other nobles, beaten unconscious, and handed over to the English. Learning of his father's treachery, the younger Bruce disowns his father.

In London, Wallace is brought before the English magistrates and tried for high treason. He denies the charges, declaring that he had never accepted Edward as his King. The court responds by sentencing him to be "purified by pain." After the sentencing, a shaken Wallace prays for strength during the upcoming torture and rejects a painkiller brought to him by Isabelle. Afterwards, the princess goes to her husband and father-in-law, begging them to show mercy. Prince Edward, speaking for the now terminally ill and mute Longshanks, tells his wife that the king will take pleasure in Wallace's death. Isabelle verbally lambastes her husband and father-in-law, then informs the weakened Longshanks of her pregnancy with Wallace's child and swears that Edward will not last long as king.

Meanwhile, Wallace is taken to a London square for his torture and execution by beheading. He refuses to submit to the king and beg for mercy despite being half hanged, racked, castrated, and disemboweled publicly. Awed by Wallace's courage, the Londoners watching the execution begin to yell for mercy, and the magistrate offers him one final chance for mercy. Using the last strength in his body, the defiant William instead shouts, "Freedom!" Just as he is about to be beheaded, Wallace sees an image of Murron in the crowd smiling at him, before the blow is struck.

In 1314, Robert the Bruce, now a king and still guilt-ridden over Wallace's betrayal, leads a strong Scottish army and faces a ceremonial line of English troops at the fields of Bannockburn where the English are to accept him as the rightful ruler of Scotland. Just as he is about to ride to accept the English endorsement, the Bruce turns back to his troops. Invoking Wallace's memory, he urges his charges to fight with him as they did with Wallace. Robert then turns toward the English troop line and leads a charge toward the English, who were not expecting to fight. The film ends with Wallace's voice intoning that the Scottish won their freedom in this battle.

Cast

- Mel Gibson as William Wallace, the main protagonist. When his family is killed by the English, he leaves Scotland and travels with his uncle. Upon returning, he falls for a local girl whom he later marries. After his wife is killed by the English, he starts an uprising demanding justice that leads to a war for independence.

- Patrick McGoohan as King Edward I of England, the main antagonist. Nicknamed "Longshanks" for his height over 6 feet, the King of England is determined to ruthlessly put down the Scottish threat and ensure his kingdom's sovereignty. Despite serving as the film's villain, he and Wallace do not share a single scene throughout.

- Angus Macfadyen as Robert the Bruce. Son of the elder Bruce and claimant to the throne of Scotland, he is inspired by Wallace's dedication and bravery.

- Brendan Gleeson as Hamish Campbell. Wallace's childhood friend and captain in Wallace's army, he is often short-sighted and thinks with his fists.

- Sophie Marceau as French Princess Isabelle, who sympathizes with the Scottish and admires Wallace.

- Peter Hanly as Prince Edward. The son of King Edward and husband of Princess Isabelle through arranged marriage.

- Ian Bannen as the elder Robert the Bruce. Unable to seek the throne personally due to his disfiguring leprosy, he pragmatically schemes to put his son on the throne of Scotland despite the claims of the Balliol clan to the throne.

- James Cosmo as Campbell the Elder. The father of Hamish Campbell and captain in Wallace's army.

- Catherine McCormack as Murron MacClannough, the executed wife of Wallace. Her name was changed from Marion Braidfute in the script so as to not be confused with the Maid Marian of Robin Hood note.

- David O'Hara as Stephen. An Irish recruit among Wallace's army, he endears himself to Wallace with his humor, which may or may not be insanity. He professes to be the most wanted man on "his" island, and claims to speak to God personally. He becomes Wallace's protector, saving his life several times.

- Brian Cox as Argyle. After the death of Wallace's father and brother, Argyle takes Wallace as a child into his care, promising to teach the boy how to use a sword after he learns to use his head. Cox also had a role in another period Scottish film, Rob Roy, which was released the same year.

- James Robinson as young William Wallace. The 10-year old actor reportedly spent weeks trying to copy Gibson's mannerisms for the film.

Conception

The script for Braveheart was based mainly on Blind Harry's 15th century epic poem, The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace. In defending his script against criticism, Randall Wallace has said, "Is Blind Harry true? I don't know. I know that it spoke to my heart and that's what matters to me, that it spoke to my heart."[1]

Production

Gibson's company Icon Productions had difficulty raising enough money even if he were to star in the film. Warner Bros. was willing to fund the project on the condition that Gibson sign for another Lethal Weapon sequel, which he refused. Paramount Pictures only agreed to American and Canadian distribution of Braveheart after 20th Century Fox partnered for international rights.[2]

While the crew spent six weeks shooting on location in Scotland, the major battle scenes were shot in Ireland using members of the Irish Army Reserve as extras. To lower costs, Gibson had the same extras portray both armies. The opposing armies are made up of reservists, up to 1,600 in some scenes, who had been given permission to grow beards and swapped their drab uniforms for medieval garb.[3]

According to Gibson, he was inspired by the big screen epics he had loved as a child, such as Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus and William Wyler's The Big Country.

Gibson toned down the film's battle scenes to avoid an NC-17 rating from the MPAA.[4]

In addition to English being the film's primary language, French, Latin, and Scottish Gaelic are also spoken.

Release and reception

Box office

On its opening weekend, grossed US$9,938,276 in the United States and $75.6 million in its box office run in the United States and Canada.[5] Worldwide, the movie grossed over $210 million and was the 18th highest grossing film of 1995.[5]

Depiction

The film's depiction of the Battle of Stirling Bridge is often considered one of the greatest movie battles in cinema history.[6][7]

Around the world

The film generated huge interest in Scotland and in Scottish history, not only around the world, but also in Scotland itself. Fans come from all over the world to see the places in Scotland where William Wallace fought for Scottish freedom, and also to the places in Scotland and Ireland to see the locations used in the film. At a Braveheart Convention in 1997, held in Stirling the day after the Scottish Devolution vote and attended by 200 delegates from around the world, Braveheart author Randall Wallace, Seoras Wallace of the Wallace Clan, Scottish historian David Ross and Bláithín FitzGerald from Ireland gave lectures on various aspects of the film. Several of the actors also attended including James Robinson (Young William), Andrew Weir (Young Hamish), Julie Austin (the young bride) and Mhairi Calvey (Young Murron).

Academy Awards

The movie was nominated for 10 Oscars and won 5.

| Award | Person | |

| Best Picture | Mel Gibson Alan Ladd, Jr. Bruce Davey Stephen McEveety |

|

| Best Director | Mel Gibson | |

| Best Cinematography | John Toll | |

| Best Sound Editing | Lon Bender Per Hallberg |

|

| Best Makeup | Peter Frampton Paul Pattison Lois Burwell |

|

| Nominated: | ||

| Best Original Screenplay | Randall Wallace | |

| Best Original Score | James Horner | |

| Best Sound | Andy Nelson Scot Millan Anna Behlmer Brian Simmons |

|

| Best Film Editing | Steven Rosenblum | |

| Best Costume Design | Charles Knode | |

Cultural effects

The film is credited by Lin Anderson, author of Braveheart: From Hollywood To Holyrood as having played a significant role in affecting the Scottish political landscape in the mid to late 1990s.[8]

Wallace Monument

In 1997, a 12-ton sandstone statue of Mel Gibson, depicted as the Braveheart character of William Wallace, was placed in the car park at the foot of the Wallace Monument near Stirling, Scotland. The statue, which includes the word "Braveheart" on Wallace's shield, the work of sculptor Tom Church, was the cause of much controversy and one local resident stated that it was wrong to "desecrate the main memorial to Wallace with a lump of crap."[9] In 1998 the statue was vandalised by someone who smashed the face in with a hammer. After repairs were made, the statue was encased in a cage at night to prevent further vandalism. This only incited more calls for the statue to be removed as it then appeared that the Gibson/Wallace figure is imprisoned. The statue had been described as "among the most loathed pieces of public art in Scotland."[10] In 2008, the statue was returned to its sculptor to make room for the building of a new visitor centre.[11]

Criticism

Accusations of anti-gay depictions

The depiction of Prince Edward as an effeminate homosexual in the film drew accusations of homophobia against Gibson. He replied that "The fact that King Edward throws this character out a window has nothing to do with him being gay. ... He's terrible to his son, to everybody."[12] Gibson defended his depiction of Prince Edward as weak and ineffectual, saying,

| “ | I'm just trying to respond to history. You can cite other examples – Alexander the Great, for example, who conquered the entire world, was also a homosexual. But this story isn't about Alexander the Great. It's about Edward II.[13] | ” |

Gibson asserted that the reason the king killed his son’s lover was because the king was a “psychopath,”[14] and he expressed bewilderment that some audience members would laugh at this murder:

| “ | We cut a scene out, unfortunately . . . where you really got to know that character (Edward II) and to understand his plight and his pain. . . . But it just stopped the film in the first act so much that you thought, 'When's this story going to start?'[15] | ” |

Anglophobia

Braveheart has been accused of Anglophobia. The film was referred to in The Economist as "xenophobic"[16] and John Sutherland writing in the Guardian stated that, "Braveheart gave full rein to a toxic Anglophobia".[17] Colin MacArthur, author of Brigadoon, Braveheart and the Scots: Distortions of Scotland in Hollywood Cinema calls it "a f***in’ [sic] atrocious film"[18] and writes that a worrying aspect of the film is its appeal to "(neo-) fascist groups and the attendant psyche.[19] According to The Times, MacArthur said "the political effects are truly pernicious. It’s a xenophobic film."[18] The Independent has noted, "The Braveheart phenomenon, a Hollywood-inspired rise in Scottish nationalism, has been linked to a rise in anti-English prejudice".[20]

Historical inaccuracies

Historian Elizabeth Ewan describes Braveheart as a film which "almost totally sacrifices historical accuracy for epic adventure".[21]

The title of the film is also historically inaccurate as the "brave heart" refers in Scottish history to that of Robert the Bruce, and an attribution by William Edmondstoune Aytoun, in his poem Heart of Bruce, to Sir James the Good: "Pass thee first, thou dauntless heart, As thou wert wont of yore!", prior to Douglas's demise at the Battle of Teba in Andalusia.[22]

Historian Sharon Krossa notes that the film contains numerous historical errors, beginning with the wearing of belted plaid by Wallace and his men. She points out that in the period in question, "... no Scots ... wore belted plaids (let alone kilts of any kind)."[23] Moreover, when Highlanders finally did begin wearing the belted plaid, it was not "in the rather bizarre style depicted in the film."[23] She compares the inaccuracy to "... a film about Colonial America showing the colonial men wearing 20th century business suits, but with the jackets worn back-to-front instead of the right way around."[23] She remarks "The events aren't accurate, the dates aren't accurate, the characters aren't accurate, the names aren't accurate, the clothes aren't accurate—in short, just about nothing is accurate."[24]

Historian Alex von Tunzelmann writing in The Guardian noted several historical inaccuracies: William Wallace never met Princess Isabella, as she married King Edward II three years after Wallace's death (and was no older than ten when Wallace died); because her marriage to Edward took place after he had ascended the throne, she never held the title Princess of Wales; and the primae noctis decree was never used by King Edward.[25] In 2009, the film was second on a list of "most historically inaccurate movies" in The Times.[26]

The portrayal of Robert I of Scotland (Robert the Bruce) in the film is considered by historians to be wildly inaccurate. In particular his taking the field on the English side in the battle of Falkirk is completely fictitious; Bruce was not present at Falkirk. Although he repeatedly changed alliances between the rebels and the English, mostly for political reasons, Bruce never betrayed Wallace directly, and Wallace was known to have been a complete supporter of Bruce. The film's depiction of the Battle of Stirling Bridge shows the Scots facing off the English on a flat plain on equal terms, when in reality, it took place at a bridge where the outnumbered Scots were able to concentrate their forces on the overextended English who were in the process of crossing the bridge.

In the 2007 humorous non-fictional historiography An Utterly Impartial History of Britain, author John O'Farrell notes that Braveheart could not have been more historically inaccurate, even if a "Plasticine dog" had been inserted in the film and the title changed to William Wallace and Gromit.

Screenwriter Randall Wallace is very vocal about defending his script from historians who have dismissed the film as a Hollywood perversion of actual events. In the DVD audio commentary of Braveheart, director Mel Gibson acknowledges many of the historical inaccuracies but defends his choices as director, noting that the way events were portrayed in the film were much more "cinematically compelling" than the historical and/or mythical fact.

Soundtrack

The soundtrack for Braveheart was composed and conducted by James Horner, and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra. The soundtrack, comprising 77 minutes of background music taken from significant scenes in the film, was noticeably successful, and Horner produced a follow-up soundtrack in 1997 titled More Music from Braveheart. International and French versions of the soundtrack have also been released.

Braveheart (1995)

- Main Title (2:51)

- A Gift of a Thistle (1:37)

- Wallace Courts Murron (4:25)

- The Secret Wedding (6:33)

- Attack on Murron (3:00)

- Revenge (6:23)

- Murron’s Burial (2:13)

- Making Plans/ Gathering the Clans (1:52)

- “Sons of Scotland” (6:19)

- The Battle of Stirling (5:57)

- For the Love of a Princess (4:07)

- Falkirk (4:04)

- Betrayal & Desolation (7:48)

- Moray’s Dream (1:15)

- The Legend Spreads (1:09)

- The Princess Pleads for Wallace’s Life (3:38)

- “Freedom”/The Execution/ Bannockburn (7:24)

- End Credits (7:16)

References

- ↑ Anderson, Lin. "Braveheart: From Hollywood to Holyrood." Luath Press Ltd. (2005): 27.

- ↑ Michael Fleming (2005-07-25). "Mel tongue-ties studios". Daily Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117926430.html.

- ↑ Braveheart 10th Chance To Boost Tourism In Trim, Meath Chronicle, August 28, 2003 . Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ↑ "Mel talks to Seoras Wallace". Magic Dragon Multimedia. http://www.magicdragon.com/Wallace/Brave5.html. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Braveheart (1995)". Boxofficemojo.com. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=braveheart.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "The best -- and worst -- movie battle scenes". CNN. 2007-03-30. http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/03/29/movie.battles/index.html. Retrieved 2007-04-01.

- ↑ Noah Sanders (2007-03-28). "Great Modern Battle Scenes - Updated!". Double Viking. http://www.doubleviking.com/great-modern-battle-scenes-4361-p.html. Retrieved 2007-04-02.

- ↑ Boztas, Senay (2005-07-31). "Wallace movie ‘helped Scots get devolution’ - [Sunday Herald]". Braveheart.info. http://www.braveheart.info/news/2005/sunday_herald/2007-07-31/51063.html. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ By Hal G.P. Colebatch on 8.8.06 @ 12:07AM. "The American Spectator". Spectator.org. http://www.spectator.org/dsp_article.asp?art_id=10191. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Kevin Hurley (19 September 2004). "They may take our lives but they won't take Freedom". Scotland on Sunday. http://scotlandonsunday.scotsman.com/williamwallace/They-may-take-our-lives.2565370.jp. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Wallace statue back with sculptor". BBC News. 16 October 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/tayside_and_central/8310614.stm. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ↑ "Gay Alliance has Gibson's 'Braveheart' in its sights", Daily News, May 11, 1995, http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/gossip/1995/05/11/1995-05-11_gay_alliance_has_gibson_s__b.html, retrieved February 13, 2010

- ↑ The San Francisco Chronicle, May 21, 1995, “Mel Gibson Dons Kilt and Directs” by Ruth Stein

- ↑ Matt Zoller Seitz. "Mel Gibson talks about Braveheart, movie stardom, and media treachery". Dallas Observer. http://www.dallasobserver.com/Issues/1995-05-25/film/film_3.html. Retrieved 2008-01-27.

- ↑ USA Today, May 24, 1995, “Gibson has faith in family and freedom” by Marco R. della Cava

- ↑ "Economist.com". Economist.com. 2006-05-18. http://www.economist.com/PrinterFriendly.cfm?story_id=6941798. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ "John Sutherland". The Guardian (London). 2003-08-11. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2003/aug/11/religion.world. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Braveheart battle cry is now but a whisper". London: Times Online. 2005-07-24. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/scotland/article546776.ece. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Colin, McArthur (2003). Brigadoon, Braveheart and the Scots: Distortions of Scotland in Hollywood Cinema. I.B.Tauris. p. 5. ISBN 1860649270. http://books.google.com/books?id=XMOUo5VUkoQC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Brigadoon,+Braveheart+And+The+Scots&ei=mYF6SYvYMaKIyASPsaG2Bg#PPA5,M1.

- ↑ Burrell, Ian (1999-02-08). "Most race attack victims `are white': The English Exiles - News". London: The Independent. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/most-race-attack-victims-are-white-the-english-exiles-1069506.html. Retrieved 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Ewan, Elizabeth. "Braveheart." American Historical Review 100, no. 4 (October 1995): 1219–21.

- ↑ http://infomotions.com/etexts/gutenberg/dirs/1/0/9/4/10945/10945.htm

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Krossa, Sharon L.. "Braveheart Errors: An Illustration of Scale". http://medievalscotland.org/scotbiblio/bravehearterrors.shtml. Retrieved 2009-06-15.

- ↑ Krossa, Sharon L.. "Regarding the Film Braveheart". http://www.medievalscotland.org/scotbiblio/braveheart.shtml. Retrieved 2009-11-26.

- ↑ von Tunzelmann, Alex (2008-07-30). "Braveheart: dancing peasants, gleaming teeth and a cameo from Fabio". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2008/jul/30/3. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ White, Caroline (August 4, 2009). "The 10 most historically inaccurate movies". London: The Times. http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/tol/arts_and_entertainment/film/article6738785.ece. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

External links

- Braveheart at the Internet Movie Database

- Braveheart at Allmovie

- Braveheart at Rotten Tomatoes

- Braveheart at Box Office Mojo

- Braveheart at Metacritic

- Roger Ebert's review of Braveheart

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Forrest Gump |

Academy Award for Best Picture 1995 |

Succeeded by The English Patient |

|

|||||

|

|||||